Any player who has played rugby at any level around the world knows the joke. Towards the end of the game, you could turn around and look at your mates, all bloodied, battered and caked in mud, and know they had all shared the same experience as you.

Sometimes, the feeling was religious in intensity.

There was always an exception to the rule.

Who was that fellow in a far-flung corner of the field, still resplendent in his pristine kit – and quite possibly, filing his nails and coiffing his hair?

The answer was ‘the winger’ – the player whose sole job was to await his one chance of the of the day, and crown the efforts of those at the rock face with a moment of individual magic and a try in the corner. That done, he could retire to the hair salon for good.

In the modern professional game, the landscape looks very different. The wingman can no longer hold off on the laundry for one more week because the shorts are still as good as new. Now, he or she has to get their hands, and every other part of their body, resoundingly dirty.

Wings have grown in size: think Julian Savea or Caleb Clarke or the great Jonah Lomu for the All Blacks, think George North and Josh Adams for Wales, or Lote Tuqiri, Wendell Sailor and Marika Koroibete for Australia. Those players were, or are the biggest, and most powerful players in the entire backline.

It is an indicator of just how far the role of the modern wing has evolved. Wings are expected to get involved in far more of the play on both attack and defence, and provide that crucial extra body on both sides of the ball.

On defence, they have to be able to play as a part of the backfield ‘pendulum’ shifting from wing into fullback, and they need to be able to kick and catch the high ball. On attack, they need to be able to follow the attack infield from the blindside wing and pick the moment to insert themselves into the play with lethal force.

The wing carrying the flag for the Wallabies is ex-Melbourne Storm star Marika Koroibete. Even before the 2019 World Cup, his (then) coach at the Melbourne Rebels, Dave Wessels, was already hailing him as “by quite some way, the premier winger in Australia”.

“He’s the quiet assassin.

“I think his try-scoring, his ball-carrying – all the obvious stuff everybody knows how good he is at those things – but we are really pleased about his efforts off the ball, his work rate off the ball, his work in contact.

“He’s really developing into a world-class winger.”

(Photo by Albert Perez/Getty Images)

At almost 100 kilograms, Koroibete has always had size, speed and power to burn. Since Wessels’ comments in 2019, he has improved measurably.

What really counts in the modern game for a wing is not just finishing moves, it is the area Dave Wessels pinpoints – work rate and efforts made off the ball. A wing in 2021 has to be prepared to put himself about, and get his shorts dirty.

The impact of a workaholic wing can be illustrated by reference to not just Marika Koroibete, but also comparable contemporaries like Caleb Clarke in New Zealand, and the ‘bolter’ in the recent British and Irish Lions squad from Scotland-via-South Africa, Duhan van der Merwe.

During the 2020 Tri Nations tournament, Koroibete had the third most ball-carries among the Wallabies – 33 in four games, behind only Harry Wilson (36) and Hunter Paisami (39). His average metres per carry was higher than both, at 6.2 metres per shot.

You don’t get to make that kind of impact by hugging your side-line all game long, and 25 per cent of Koroibete’s carries came close to the ruck – on pick and go plays, or playing short off his scrumhalf.

One measure of the modern wing’s success is his desire and ability to operate on the ‘wrong’ side of the field on attack, away from his natural touch-line. One of the first candidates for extra work rate is in the early phases from lineout or scrum.

In these examples, Marika is hugging the 10 (or the 10 channel), not the sideline: first receiving a nice reverse pass from Brandon Paenga-Amosa to penetrate a gap close to the lineout maul in Bledisloe 4, then faithfully following James O’Connor into midfield and back out to the short-side in Bledisloe 1.

It is the sort of position Koroibete adopts regularly for the Rebels in Super Rugby.

From this spot, he can attend the ruck, pick and go straight ahead if ruck delivery is quick, or drop out to either side of the breakdown off a short pass. The New Zealand attack received a surge of positive voltage from the inclusion of Caleb Clarke in these scenarios at Bledisloe 2.

Clarke piggy-backs the halfback in towards the ruck, then drops off to the ‘wrong’ side to attack the disorganised Wallaby forwards at the edge of the breakdown.

Another major aspect of the wing’s role in the professional game was illustrated to perfection by Clarke later in the same match.

The wing now has to be able to play the role of a fullback, receiving the high ball in the centre of the field and initiating a counter-attack.

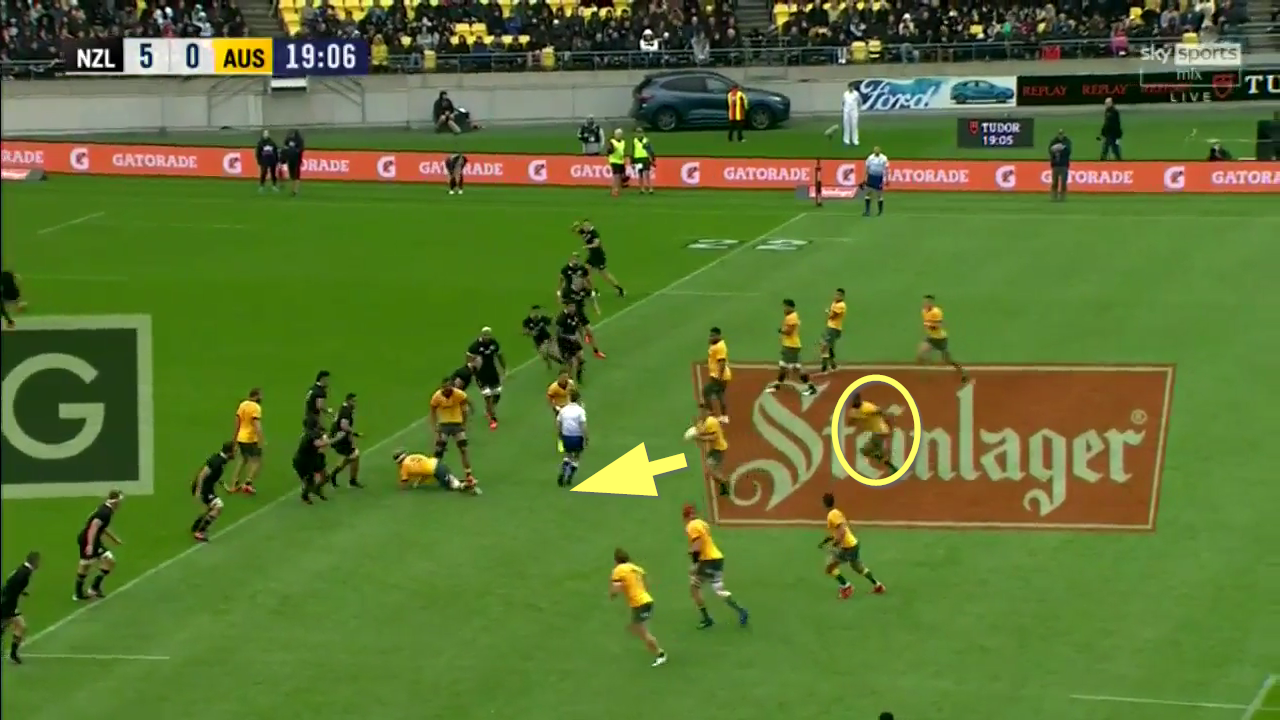

One of the most piquant moments of the entire Bledisloe series for a connoisseur of wing play, occurred in the third game between the All Blacks and Wallabies.

Both Clarke and Koroibete start on the ‘wrong’ side of this play, with Clarke shifting around to the right from the left wing on attack, and Koroibete bolstering the 10 channel on defence before making a magnificent last-ditch tackle to prevent a try in the corner. That is work rate off the ball, in a nutshell.

Even when they are playing on their natural side, this prototype modern wing is frequently not the last attacker on the edge, trying to keep the shorts clean.

In both cases (for Australia against England at the World Cup, and for the Rebels against the Highlanders in Trans-Tasman), Koroibete is not the last man in attack, but playing inside his number 13 (Jordan Petaia/Stacey Ili) with a back-rower on the edge (Michael Hooper/Michael Wells). The idea is to get a fast, powerful man matched up on a slower opponent, preferably a forward, and still have enough quality support left in reserve if he is tackled.

Perhaps the clearest example of the raised levels of expectation for the contemporary wing, in terms of leaving his spot and finding work off the ball, occurred in the recent British and Irish Lions warm-up against Japan.

As ex-Springbok legend Bryan Habana eloquently illustrated (with the help of the graphics team and a view from behind the posts) in the TV commentary, it is Scotland wing Duhan van der Merwe’s work off the ball which gets the job done.

In the course of the 20 seconds that the sequence lasts, Van der Merwe runs across the entire width of the field before providing the last unmarked attacker on the extreme right-hand side.

Any self-respecting wingman of the amateur era would already have turned away in disgust, but of such stuff professional wing dreams are made.

Summary

One of the strongest areas of the visiting French touring side is likely to be in the back three and especially on the wing, where Teddy Thomas, Damian Penaud and Alivereti Raka are all established stars.

It is not too hard to envisage Raka, in particular, playing the role of a Koroibete or a Clarke in the series to come. Work off the ball is one of the areas of paramount importance in rugby as it is played today, and the blindside wing is one of the best spots from which to get it.

If the Wallabies can win that battle with their starting duo of Koroibete and Tom Wright, it will go a long way towards winning the war as a whole. If you can beat an inexperienced team in their most seasoned area, it is an excellent harbinger of overall success.

Sports opinion delivered daily

function edmWidgetSignupEvent() {

window.roarAnalytics.customEvent({

category: ‘EDM’,

action: ‘EDM Signup’,

label: `Shortcode Widget`,

});

}

Even the greatest wingers of the amateur days would probably look at some of the positions their professional descendants take up and shake their heads, or marvel at the metamorphosis the game has undergone.

The modern wing is no artistic dilettante, waiting for his opportunity to take centre stage. They are just one of the boys (or girls), with blood on their faces and mud on their backsides.

Those pristine shorts can be hung up in a museum somewhere – the dusty relic of the distant past. Nothing more.

Original source: https://www.theroar.com.au/2021/07/07/why-the-modern-game-has-no-place-for-a-wing-with-clean-shorts/

source https://therugbystore.com.au/why-the-modern-game-has-no-place-for-a-winger-with-clean-shorts/

No comments:

Post a Comment